New research by a University of New England (UNE) palaeontologist has uncovered the first known evidence of multi-species herding behaviour in dinosaurs, based on fossilised footprints discovered in Canada’s Dinosaur Provincial Park.

The discovery, made in July 2024 during an international field course, has been published in the journal PLOS One and reveals 76-million-year-old tracks from different dinosaur species walking side by side — a breakthrough in understanding dinosaur social behaviour.

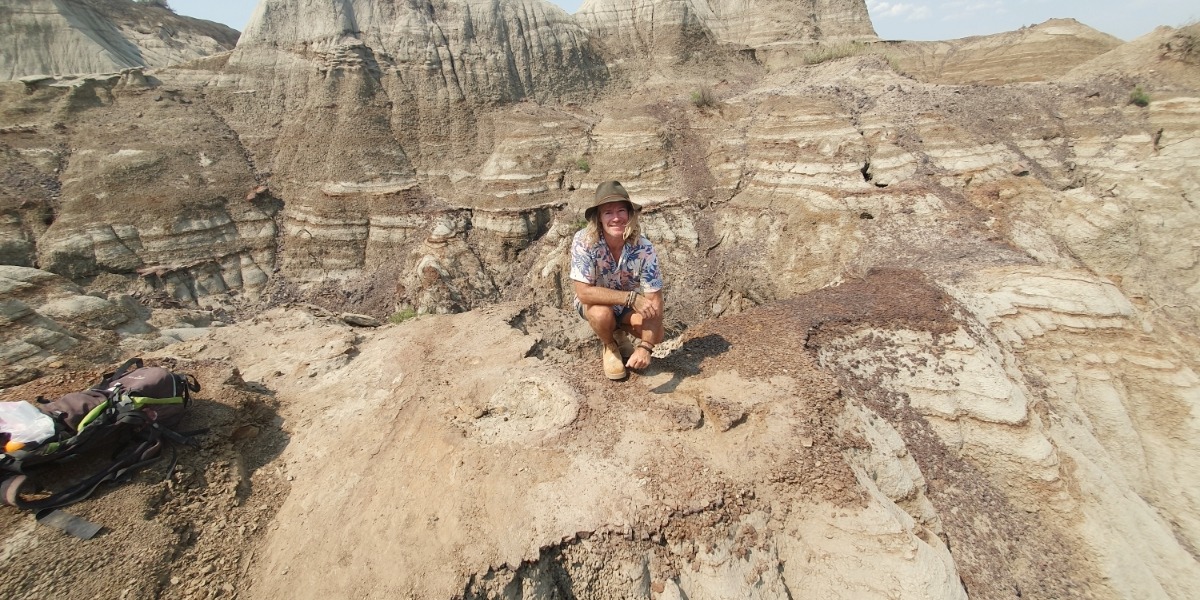

Dr Phil Bell, from UNE, worked alongside Dr Brian Pickles of the University of Reading and Dr Caleb Brown of the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology to excavate a 29-square-metre section of the site. They uncovered 13 ceratopsian (horned dinosaur) tracks from at least five individuals walking together, with what is believed to be an ankylosaurid (armoured dinosaur) moving among them. A single footprint from a small meat-eating dinosaur was also found, and the tracksite extends further into the hillside.

“It was incredibly exciting to be walking in the footsteps of dinosaurs 76 million years after they laid them down,” said Dr Pickles. “Using the new search images for these footprints, we have been able to discover several more tracksites within the varied terrain of the Park, which I am sure will tell us even more about how these fascinating creatures interacted with each other and behaved in their natural environment.”

Dr Bell, who has spent nearly two decades studying dinosaur fossils in the Park, said the find opened a new chapter in dinosaur research.

“I’ve collected dinosaur bones in Dinosaur Provincial Park for nearly 20 years, but I’d never given footprints much thought. This rim of rock had the look of mud that had been squelched out between your toes, and I was immediately intrigued,” Dr Bell said.

The team was particularly surprised to find two large tyrannosaur tracks moving side-by-side and perpendicular to the herd, suggesting the predators may have been watching or stalking the herbivores.

“The tyrannosaur tracks give the sense that they were really eyeing up the herd, which is a pretty chilling thought, but we don’t know for certain whether they actually crossed paths,” Dr Bell said.

While fossilised bones have long provided insight into the anatomy of dinosaurs, trackways can offer rare glimpses into their behaviour. The presence of different herbivorous species walking together supports a long-held hypothesis that some dinosaurs may have moved in mixed herds, similar to modern-day wildebeest and zebra on the African plains. This new tracksite is the first definitive evidence of such behaviour.

Dr Brown said the discovery highlighted the ongoing potential of even well-studied sites.

“This discovery shows just how much there is still to uncover in dinosaur palaeontology,” he said. “Dinosaur Park is one of the best understood dinosaur assemblages globally, with more than a century of intense collection and study, but it is only now that we are getting a sense for its full potential for dinosaur trackways.”

Dinosaur Provincial Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Alberta, is globally renowned for its fossil record, but footprints have been rare. The new find opens the door to further discoveries that could reshape current understanding of how dinosaurs lived and moved in their environments.

The research involved a collaborative effort between institutions including the University of Reading (UK), University of New England (Australia), Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology (Canada), Macquarie University, University of Manitoba, and University of Alberta.

The full study is available in PLOS One.

Something going on in your part of the New England people should know about? Let us know by emailing newsdesk@netimes.com.au