This is part 2 of our investigation into water quality issues in the New England. Read Part 1 here.

Ask the average Joanne on the street if they thought it was acceptable that any town in Australia did not have access to drinkable tap water and the answer will most certainly be no.

However, one of the quirks of living in very small towns is that they aren’t fond of admitting there’s a problem. They’ll talk about it amongst themselves, but rarely make a formal complaint. The same social dynamics that make smaller communities amazing places to live, where locals care about locals and will always rally to someone in need, also sometimes prevents communities asking for help from outsiders when they really need it.

The aging infrastructure of water treatment and distribution systems is a significant issue in many of these tiny communities, particularly those with hard water. It is regularly acknowledged that much of the water infrastructure in regional News South Wales is either well past its use by date, or hasn’t been effectively maintained.

However, there is a significant lack of data on the state’s regional water quality. Recent academic work reviewing the water quality in regional and remote areas found a major gap in data from New South Wales because, unlike the rest of Australia, production of annual drinking water quality reports is not a regulatory requirement for any water suppliers in New South Wales. Only 18 of 81 local water utilities in the state provide enough data to assess compliance against health-based and aesthetic guideline values of the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines.

Combine the lack of data with small populations, and the intense social pressures in smaller communities not to complain, and it is easy to understand how water quality in so many communities can be so bad for so long without anything being done.

Unheard in Uralla

The biggest disruption to water supply because of a quality concern in recent memory is the six months that Uralla was on bottled water, due to arsenic in the water as a result of low water levels in 2019.

Just like Guyra, the drought eased and supply issues were addressed, and the restrictions on drinking town water were lifted, but the underlying issues with water quality remained unaddressed.

Ruth, one of Uralla’s 3000-odd residents, is concerned about both her health and her budget because of the ongoing state of the water.

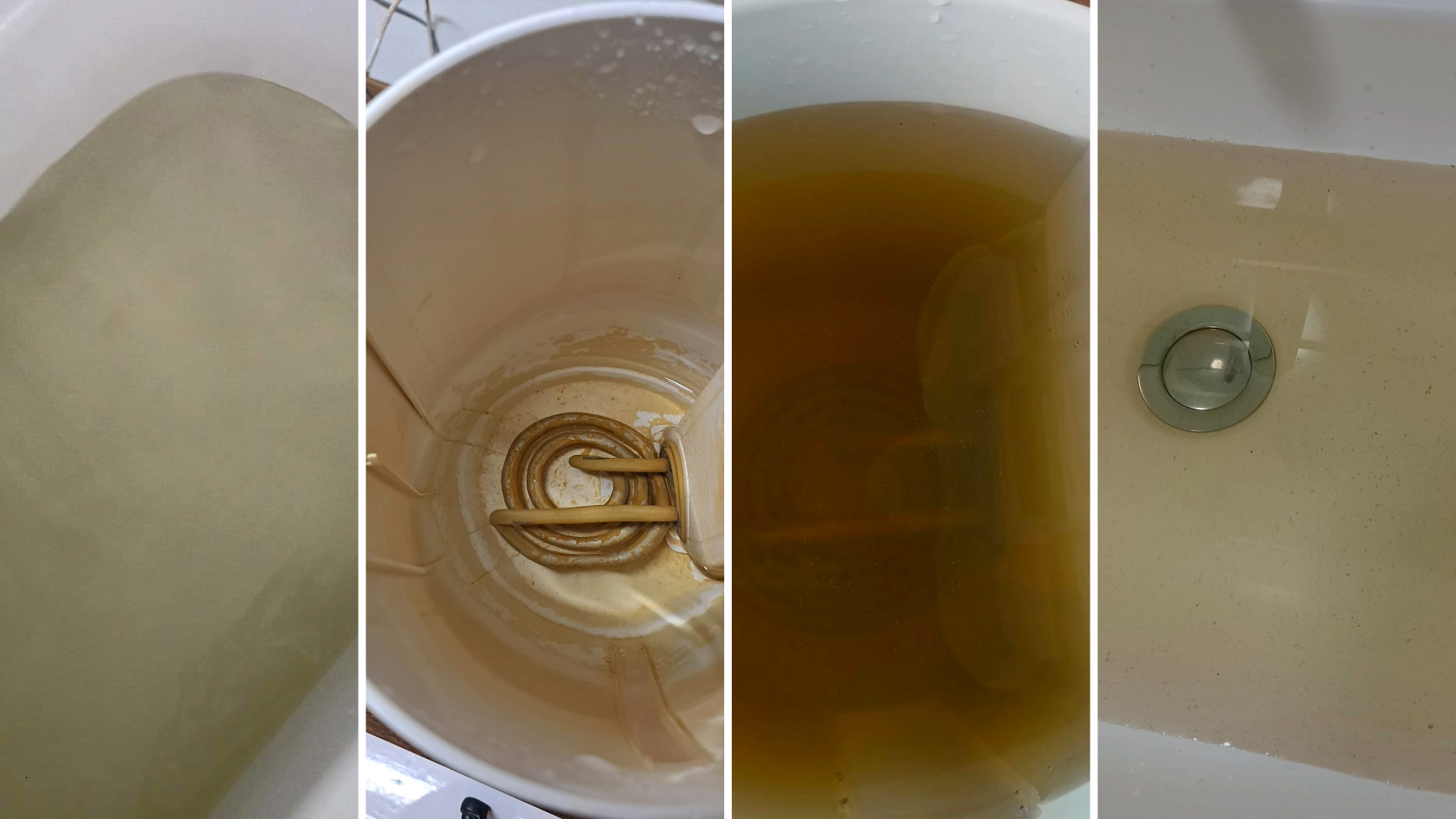

“It looks, tastes and smells foul. It’s often brown, stains the bath, toilet and appliances like kettles.”

“I can’t drink it without filtering, adding to the cost, and sometimes, I still need to add cordial to be able to drink it.”

“I can have it boiled with coffee or tea, but sometimes it still tastes of chemicals or dirt.”

“Showering or bathing in it leaves my skin dry and itchy but I guess that’s an improvement on the sliminess it used to leave.”

“I need to drink at least 2 litres per day and can’t afford to buy bottled water, so I just have to hope it’s not negatively affecting my health,” she said.

“I don’t understand why it’s such bad quality as many customer complaints to Uralla Shire Council have failed to be acknowledged let alone addressed.”

The issues with water quality in Uralla are significant enough, and have been going on long enough, for Uralla’s Facebook Groups and other media to frequently feature ads for water purification systems and rainwater tank installers.

Tony Averay, General Manager of Uralla Shire Council, says they take their commitments to provide quality drinking water very seriously.

“While there may from time to time be changes in taste, colour or smell, the water remains safe to drink.”

“Council is committed to ensuring a safe drinking water supply for our residents and we are investing significantly in improvements to our treatment systems to not only address these customer concerns but also to ensure long term water security and resilience in the face of any future drought.”

“I would encourage residents to contact Council’s Customer Service team direct on 6778 6300 with any concerns or questions they might have about drinking water so we can raise a Customer Request and provide relevant advice or investigate as appropriate.”

However, a number of people we spoke to from Uralla indicated that it is difficult to approach council, or speak out about any issues in the town, for fear of retribution.

“It’s a very small town and you can’t piss off the council,“ said one Uralla resident.

Bottles for Bundara

The arsenic issues in Uralla were just a few short months after Bundarra, also in the Uralla Shire, was also on bottled water for months. The issue there was elevated turbidity, due to higher levels of iron and manganese in the raw water supply from Taylors Pond, and an unacceptable residual chlorine level. There was also a significant leak from the town’s main reservoir.

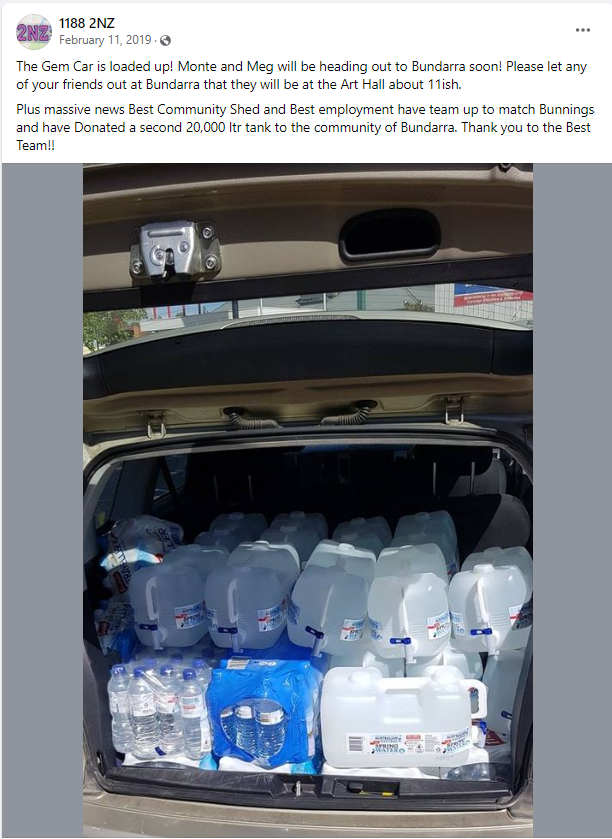

James ‘Monte’ Irvine, a former radio announcer who ran the ‘Bottles for Bundarra’ campaign with 2NZ Inverell, says he was moved to do the initiative in part because he felt Council and others in authority didn’t seem to care about the hardship having to buy water placed on Bundarra’s 400 residents.

“People were having to boil water for everything, and were being advised to only drink bottled water.”

“I saw that on the news, and decided to do something on air the next day.”

“I spoke to the Mayor of Uralla, who gave me f*** all.”

“So when he said (on air) that he couldn’t do anything, I announced that we were going to do something, and launched the Bottles for Bundarra water drive.”

By the time Monte had finished his breakfast shift that morning, they already had donations coming in. The Bundarra Lions club was helping to distribute the donated water, and everyone from schools to scouts was pitching in. Even the Inverell Shire Council helped, by letting people pay their library fines with bottled water for Bundarra.

In the final week of the six week campaign, the local Bunnings and BEST Employment had each donated a new 20,000 litre water tank to improve their neighbouring village’s water supply issues.

However, just like Guyra and Uralla, once the supply issue was sorted and the warnings lifted, the underlying quality issues persisted.

Laura says Bundarra’s town water has been disgusting for many years but it’s gotten worse recently.

“We can’t drink from the water, haven’t been able to for years. Always having to buy drinking water.”

“We also have to use strong smelling laundry detergent to get clothes to smell washed.”

“And we regularly have to clean brown limescale marks from showers and toilets which use town water.”

Abandoned in Attunga

Attunga, a small community in the Tamworth Regional Council area, population barely 500, is probably the one village in the region that has been consistently raising concerns about water quality for decades.

Attunga’s water is bore water, and very hard. The high level of calcium and magnesium in the supply is safe to drink, but is unpleasant, and locals have complained about the financial burden they’ve incurred as a result of hard water damaging their appliances – and the impact on their health.

Water hardness is an aesthetic water quality issue. High water hardness causes scale formation in pipes and heating elements (particularly hot water system and kettles), can have a negative impact on washing machine and dishwasher performance, and very hard water can have a dirty feel to it when used for bathing. If allowed to dry on a surface hard water will leave spotty marks, particularly on glass. Hardness also reacts with soaps to form soap scum rings visible on bath tubs in areas with high water hardness.

The Australian Drinking Water Guidelines limit aesthetic hardness to 200mg per litre, and Attunga’s water hardness is regularly around 300mg per litre.

In 2019 the Council spent $32,000 on a trial of a “Magnetised, Energised and Activated” water conditioning device which would treat all of the water pumped from the bores.

A survey after installation found some residents identified an improvement in the water and others didn’t. The Council left the ineffective devices in place, but have no further plans to improve water quality in Attunga.

Locals are largely just getting on with it, regularly chatting about which water softeners to use and providing advice to new residents on how to deal with the rash. But from time to time their frustration will flare, with yet another call for a better deal.

James said he’s just gotten used to throwing out kettles.

“Mate, no one cares about Attunga except the people who live here,” he said.

“One day maybe we’ll get someone who is prepared to give us decent water, until then I just buy the cheapest kettle or what have you I can and chuck em out when they’re done.”

Geriatric pipes in Glen Innes

Parts of the water system in Glen Innes are nearing a hundred years old, with the many of the original mains originally constructed in the 1930s still in use. Glen Innes also has hard water – not as bad as Attunga, but frequently fliting with the limit at an average hardness of 180mg per litre.

Glen Innes residents have been complaining about their water for many years. The main complaints are that it stinks, is frequently discoloured, and there is often a residue or sediment left behind, which builds up pretty quickly in kettles and other appliances.

Kim from Glen Innes says she has complained numerous times about the water for 13 years, but only gets excuses. Having had health issues with her kidneys, the calcium levels are what concerns her the most, but the documentation from Council indicates they don’t test for calcium.

“We are paying for unhealthy water,” she said.

“I was told [the pipes] would be replaced 13 years ago, but as yet I have not seen anything done about this filthy water.”

“We buy our water now… and we have replaced all pipes, taps and hot water system because of this rotten water.”

Glen Innes Severn Council’s Manager of Integrated Water Services, Sam Price said the discolouration is caused by rust from ageing cast iron pipes within the network, and when residents request it, Council attend the site and flush the main to remove the dirty water.

“The majority of the issues in Glen Innes relate to the reticulation network and not the actual treatment process,” Mr Price said.

“Long term residents will recall that brown water in the town mains was commonplace with regular Manganese related issues especially during summer months.“

“Glen Innes has a large number of older cast iron pipes in areas around the network, and historical Manganese problems means that there is build up on the inside of the pipes that can sometimes release and affect water quality,” Mr Price said.

“In addition to the routine maintenance, the long-term solution that Council has budgeted Capital Works funding for replacement the reticulation network and eliminate dead end mains with ring mains to improve the water quality, however, this is a lengthy process and will take many years to complete.”

In the last 5 years council has renewed approximately 5 kilometres of new mains, replacing existing cast iron mains to improve quality. The NSW Government has provided a grant of $150,000 under the Department’s Advance Operational Support Program to optimise the water treatment processes at the Glen Innes Water Treatment Plant, with work expected to be completed by March 2025.

Hope in new investment

The $150,000 for Glen Innes water quality improvements was one of ten grants Minister for Water, Rose Jackson, announced in March targeted at communities with long running water quality issues. Moree Plains Shire Council also received funding to improve water quality at Boggabilla from the same package.

“Investing in minor upgrades to existing infrastructure will enable them to respond to water quality issues faster and more effectively,” the Minister said at the time.

“The Advanced Operational Support Program also provides valuable on-the-ground training and technical assistance, at no cost to councils, to help operators tackle water challenges.”

Others are getting much more substantial improvements.

The Quipolly Water Project is a new state of the art water treatment plant and related systems that will resolve the decades long water quality issues for Werris Creek and Quirindi. Liverpool Plains Shire Council says this project is already treating water and just waiting on all the approvals to go live.

The new Tenterfield Water Treatment Plant has just been built thanks to $7 million from the NSW Government’s Safe and Secure Water Program, replacing the ageing existing water treatment plant.

The Gwydir Shire Council has started the project development stage for a new water treatment plant at Gravesend, while Inverell Shire Council has recently completed an upgrade to the Ashford water treatment plant.

And the Minister has requested the NSW Productivity Commission investigate funding options to help reduce service risk for local water utilities and provide advice to the NSW Government on a future direction.

We have seen reports before, but that the issue is on the agenda gives hope we might see all New England communities have the access to safe and drinkable water we all deserve.

Like what you’re reading? Support New England Times by making a small contribution today and help us keep delivering local news paywall-free. Donate now